Oxford, 1209: The shocked young scholar stared down at the dead body. It wasn’t clear what had taken place in that room – perhaps a blind act of passion – but at the sight of the motionless girl, he instinctively feared for his life and knew he must take flight.

As the news of the young woman’s death, most likely a prostitute, spread, the people of Oxford demanded revenge. First, the two friends who’d shared the scholar’s room were hunted down. They were dragged to the castle, then to the gallows. In normal times, the ecclesiastical authorities would have exerted themselves and claimed immunity for those in minor religious orders. The two scholars would have been saved. But in 1209, a quarrel between King John and Pope Innocent III regarding the appointment of a new Archbishop of Canterbury resulted in the King’s excommunication. He wasn’t in the mood to look kindly upon the clerical scholars, so he did nothing to prevent their hanging. Unprotected from the mob, hundreds of fearful scholars fled Oxford in search of a new place to learn. Several settled on Cambridge.

This was the story as told by the monastic chronicler, Roger of Wendover (d. 1236), and vividly reimagined by Susanna Gregory in Bloody Beginnings. Are the origins of Cambridge University due to the murder of a prostitute? We can only speculate. Yet alternative explanations are far less credible, wrote Rowland Parker in his 1983 book, Town and Gown: The 700 years’ war in Cambridge.

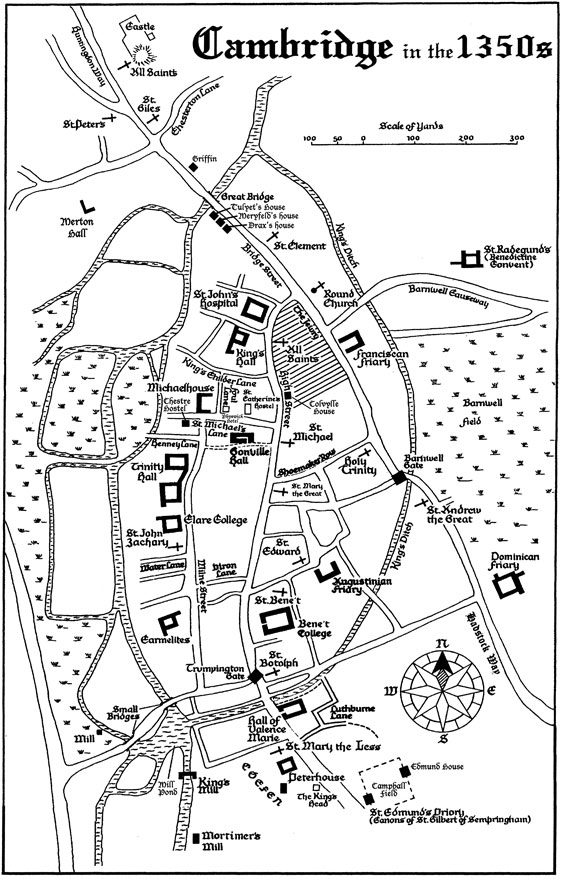

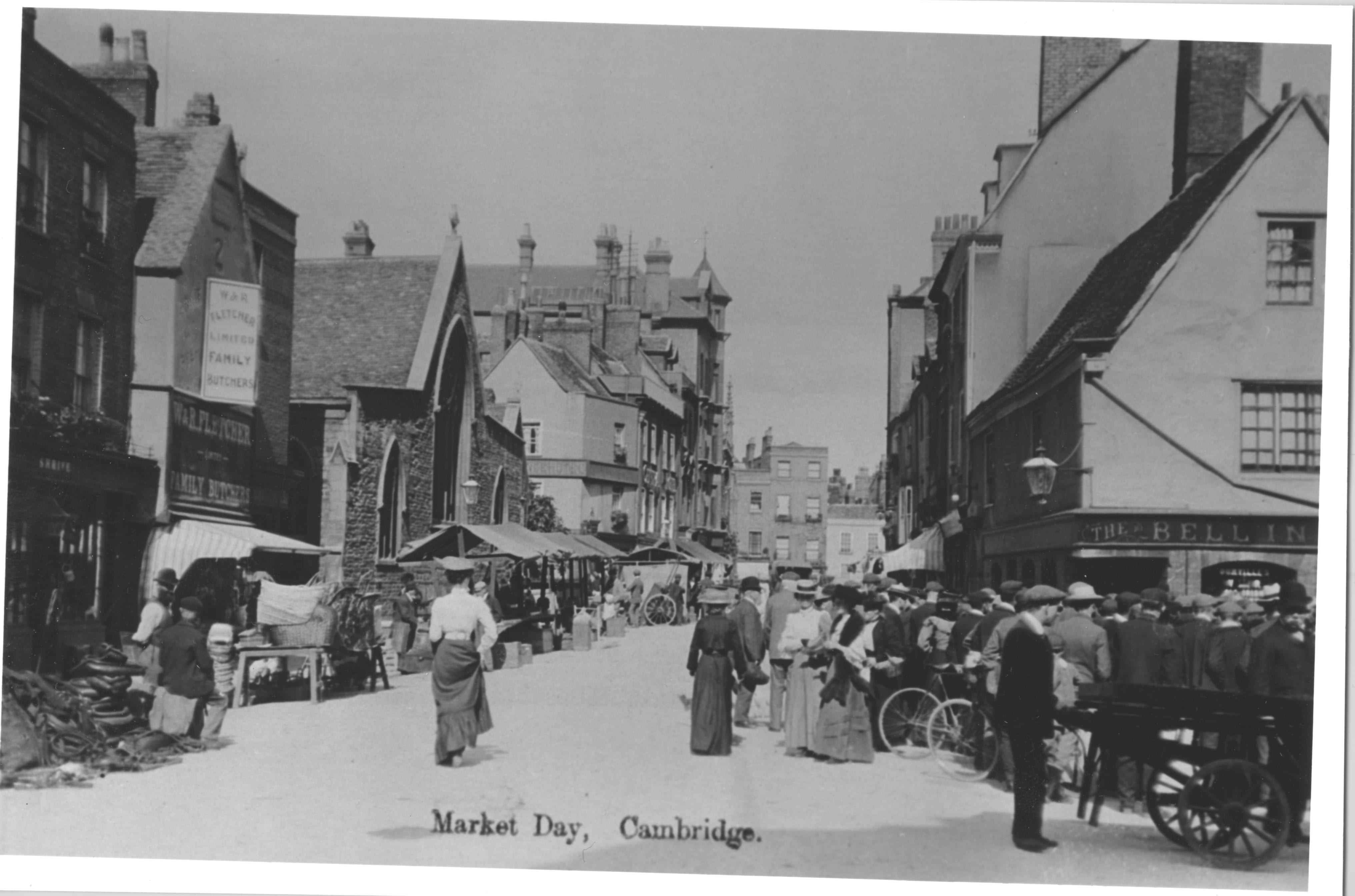

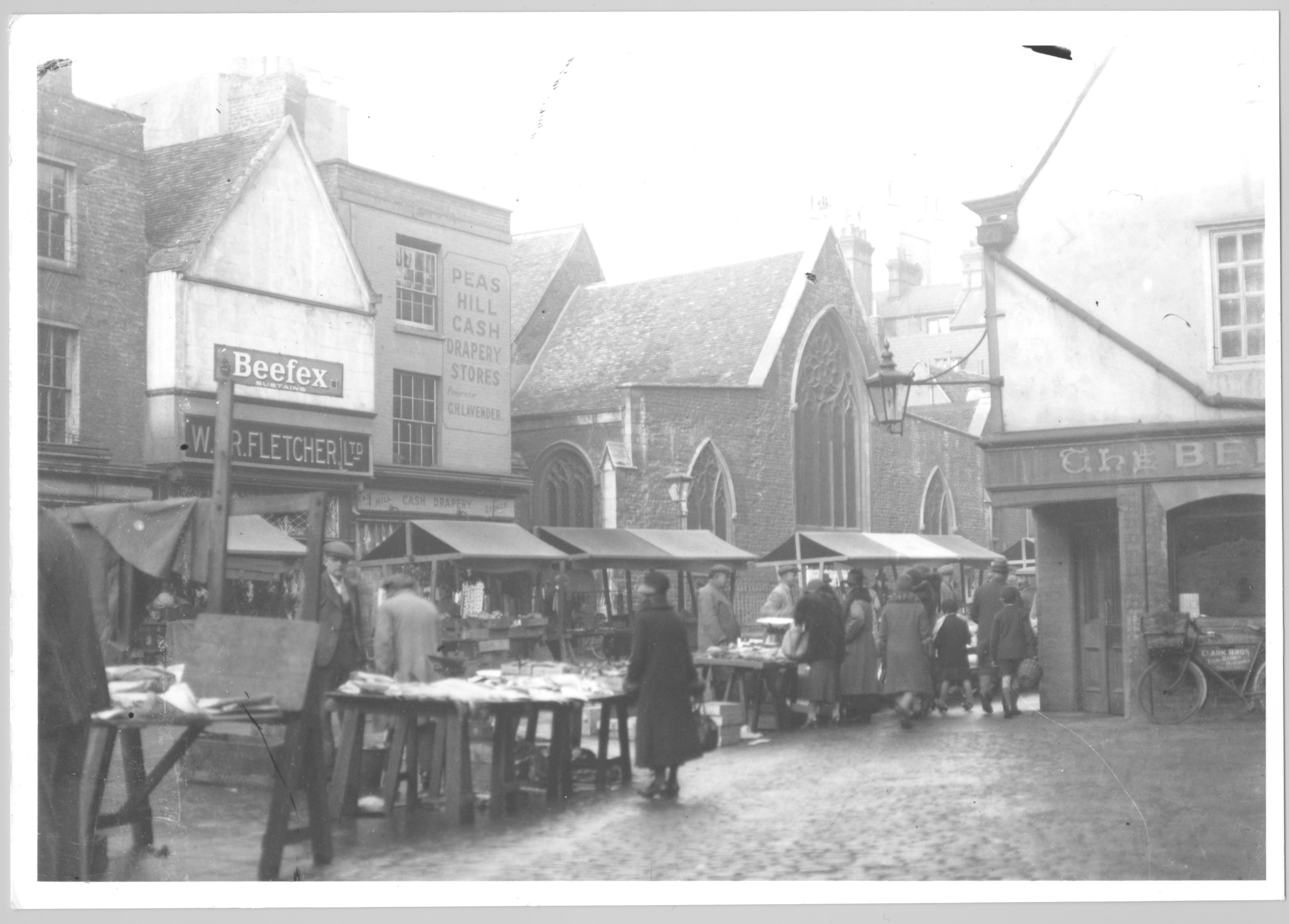

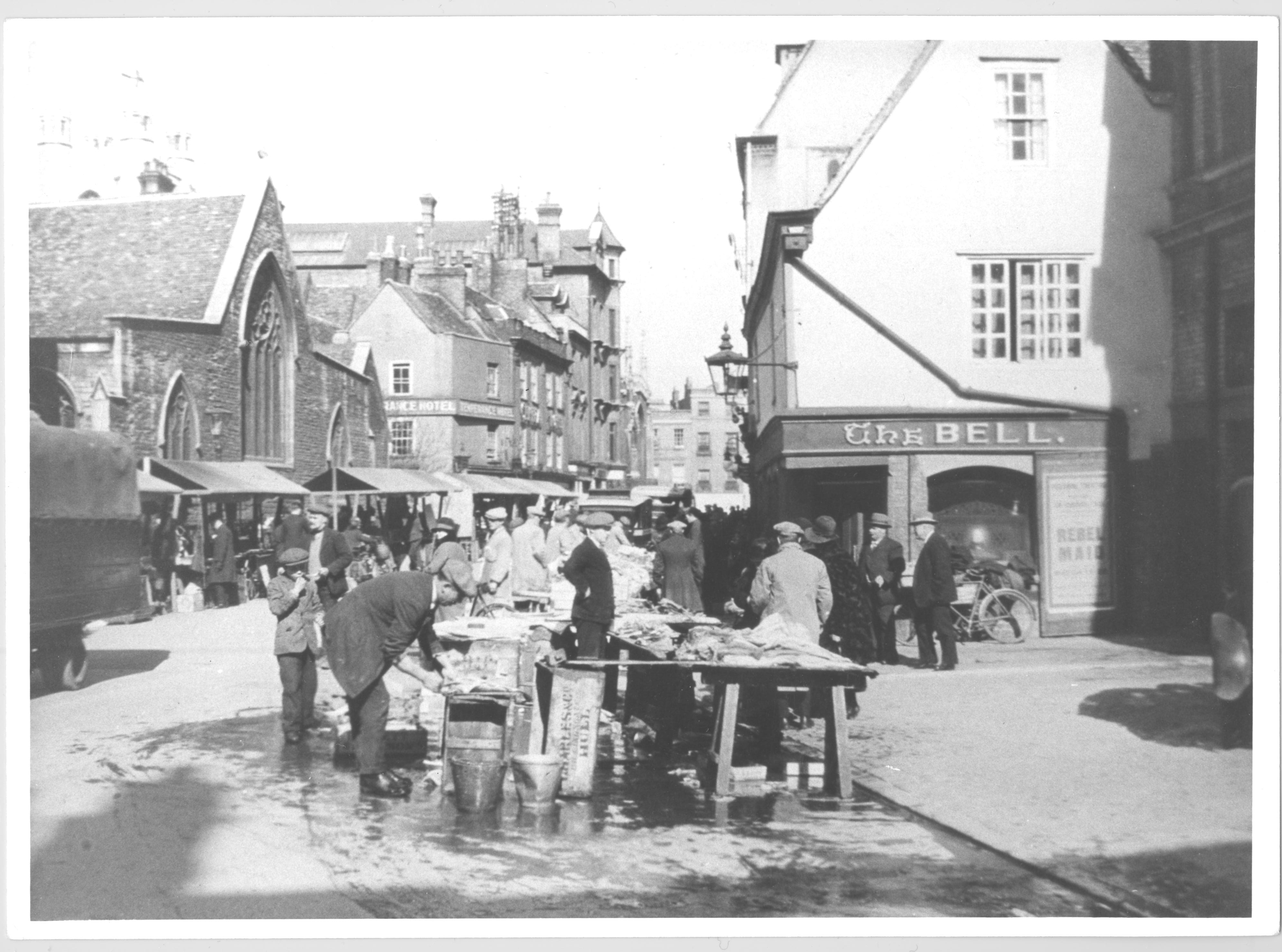

Whatever we might believe, it is a fact that the new arrivals in Cambridge were warmly welcomed. They were fair game to anyone who could turn a profit at their expense. Already, Cambridge was an important inland port. It’s then tidal river flowed into the Ouse and into the Wash. The town housed the fifth-largest Jewish community in England and was edging its way into the top twenty wealthiest towns, ranked by tax. The town had secured royal charters granting them many rights. In 1209, Cambridge, in the eyes of the law, was a fully-fledged independent town, a free borough of free men, forever.

As more and more scholars arrived, many fleeing riots in Paris, the price of spare rooms doubled, as did the cost and quality of bread and ale. No one thought the ‘foreigners’ would stay. But as their numbers swelled, the novelty of their presence altered to a deep dislike of the arrogant behaviour of exuberant, teenage boys away from home for the first time, with little supervision.

They may have been undertaking religious study, but they weren’t all meek-minded serious scholars. Many were younger sons for whom the ‘church’ would provide a living. This was the first and last opportunity for them to enjoy carefree living. Many, but not all, drank ale beyond their capacity and swaggered around town, believing they were men. They sought and seduced susceptible women, sometimes with the promise of marriage. Insolent remarks were tossed at passing townsmen of any rank. A surprising amount could be tolerated whilst their presence remained peaceful and lucrative. But this was about to change.

The history of the long drawn-out rivalry between town and gown started in 1231 when Henry III sent a letter to the mayor and bailiffs of Cambridge telling them: a multitide of students, from this country and overseas, come to our town of Cantebrigge, which pleases us very much, for it benefits our kingdom and does us honour, and you must be pleased to have the students among you. But we hear that the charges in your inns and lodging-houses are so exorbitant that, unless you do something to moderate them, the students will be obliged to leave your town, and we do not want that to happen. (Parker, p19)

Due to the many private vendettas between northern and southern scholars, and resentment from the young men of the town, bloodshed on the streets was not uncommon. In 1249, violent scuffles left several wounded or slain. Just over a decade later, a minor skirmish escalated into an alarming affray, resulting in the execution of 16 townsmen and the King pardoning 28 southern scholars. The rift with Rome had been healed. Ecclesiastical law once again protected those training for holy orders. It was the townspeople who answered to the law of the land.

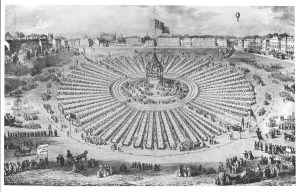

But overcharging and street brawling were not the only problems the King was invited to solve. In 1234, he issued letters patent prohibiting earls, barons, and knights from ‘tourneying’ to Cambridge for the regular tournament that took place just outside Cambridge. It turned out that the chancellor was gravely concerned that the excitement of such an event would distract the scholars.

Such tournaments took place up and down the county, with knights from all over the kingdom keen to show their prowess. The Cambridge tournament was a smaller affair. Local nobility and gentry put on fine displays of valour and chivalry. It was a spectacular day out, attracting huge numbers eager to gamble, brawl and drink. There was no way the young scholars would miss out on this event. But under the ban everyone missed out, especially the townspeople who’d once relied on the event to boost their income.

Over the next two centuries Kings and Queens eroded the towns autonomy until Cambridge was managed to suit the needs of the university. It could be argued the case remains the same today.

Sources:

British History online

Cooper, C. H. Annals of Cambridge Vol 1(1843)

Parker, R. Town and Gown – The 700 Years War in Cambridge (1983)